Yang Jinsong is part of a new generation of painters whose works record the contemporary circumstance of Beijing everyday life. However, contained in their rich imagery are frequent references to the past. In these compositions nostalgia for pre-capitalist China is palpable. Juxtaposing references to past and modern life reveals the desire to establish continuity between these extremely different periods of time, and to save information that will escape the history books. The new series of works comprise two very different visual metaphors, those of his public and private concerns. A large arm chair is the focus of several new large size (113 x 138 cm) pieces.

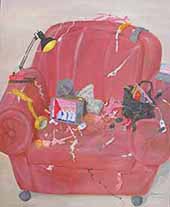

Chair, oil on canvas 113 x 138cm, May 2006 Chair, oil on canvas 113 x 138cm, May 2006

Rendered iconic in status by its central placement and size, the chair dominates the viewer. Its color, red or grey, governs the color scheme as well. Tumbling over the arms and back or nestled in the seat of the cushions are the debris of everyday life. The chair with its discarded detritus is a record of Jinsong’s personal life, past and present. The chair itself is worn out: holes and tears leak stuffing; masking tape and barbed wire incompetently repair the breaches. Mementos of the past recall Jinsong’s youth: images of Communist flags flutter outside the window, loud speakers now silent, once daily broadcast the national anthem punctuating the day at 6 am and 6 pm, worn army knapsacks used to carry his books, and a broken bust of Chairman Mao that reminds one of his famous arm chair now preserved in a museum in his home town Xiangtan, Hunan. Childhood paraphernalia perches on the arms and back of the chair- toy trains, small model planes, broken dolls, testimony to the joys that occupied a spent youth. And there are the reminders of adult everyday life— now also broken: electronic equipment, laps tops, cells phones, bent coca cola cans, toilet paper and cigarette buts. Jinsong explains in a recent interview, the image of the big soft armchair is a symbol of his life, his commitment to old fashioned values, to the comfort of the past, and time spent as a child. Now worn, nearly useless, it still stands as an icon of the past. But the modern things, he maintains, reflect the Chinese society in which he lives and reveal his concern for the government’s policies leading to the exhaustion of natural resources, pollution of the environment, and destruction of traditional moral and ethical values.

Sofa 113x138cm Jun.2006 oil on canvas Sofa 113x138cm Jun.2006 oil on canvas

Sofa 113x138cm Jun.2006 oil on canvas Sofa 113x138cm Jun.2006 oil on canvas

In style these paintings are clearly the successors to his older work: objects of everyday life are still executed in a miniaturist manner with loving attention to the details. Trained in Western realistic style as well as Chinese brush painting techniques, Jinsong’s skill in rendering representational images is evident in the details, but he obscures his skill in favor of a more direct childlike technique, though occasionally three-dimensional modeling with light and shade and drawing in perspective are apparent. Piquant incidents of color still define the objects, but the mosaic of hue and pattern is now secondary to the dominant monochrome of the massive chair, done with an expressionistic application of paint. Jinsong applies sweeping strokes of color with broad brushes. The monochrome of the textile, upon examination is not discrete; rather the paint which is mixed on the brush offers a variety of tones and delicate swatches of contrasting hues. It should be noted that this series lacks the trademarktwin portrait of he and his wife, ubiquitous in the earlier works.

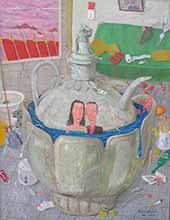

The second series is an homage to antiquity expressed through the motif antique porcelain vases which are rendered large, in frontal view, and centrally placed. Emerging from the neck of the vessel is the familiar dual image of Yang and his wife. Once again they are together in a hostile, urban, and alien environment filled with discarded consumer articles and the machines of modern technology-earth movers, planes, laptops. Dead chickens, he laughingly explains, refer to the Chicken flu, but the discarded hypodermic needles suggest more serious sinister types of occupational and environmental disease.

Wine Pot oil on canvas 60 x 80cm Jan.2006 Wine Pot oil on canvas 60 x 80cm Jan.2006

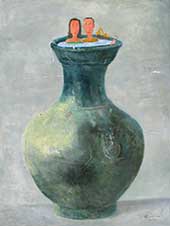

Hu Vessel no. 2 oil on canvas 90x120cm Jun.2006 Hu Vessel no. 2 oil on canvas 90x120cm Jun.2006

Significantly the couple no longer share a body, rather they comprise two half portraits, that placed side to side stand together in solidarity, but now they are physically independent of each other. Different too is the loving attention to naturalistic representation of the porcelain--a Song dynasty wine warmer, a Han dynasty glazed Hu vase. Light glistens off the porcelain surface; the image achieves monumentality through its large size and three-dimensional presence. These paintings are an act of reverence to the “old-fashioned” values of the past, to family life, to his childhood, and beloved parents. This may also be seen as at attempt to recreate China’s history lost in the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution and the upheaval of modern society in its rush to capitalism. Making these paintings, Jinsong explains, keeps him sane, relaxes and refreshes him; he does them with no anxiety.

For anxiety, emotion, and concern for a society that has lost its regard for human values are the subtext of the third type of painting--huge canvases dominated by a large gutted fish. These works are remarkable in the application of the paint, which is splashed, dripped, swathed in broad brushes, and flung like ink onto the canvas. The background is left untreated creating a raw feeling, alluding perhaps to the used paper fish are sold in. The images are icons, which for the most part are not combined with the miniaturist detail that characterized his other works. The execution of the paint imbues the painting with a kinetic energy, a frantic power; but on close inspection there are areas of great beauty and delicacy of paint mixed with sensuous areas of thick impasto.

Fish oil on canvas 250 x 360cm Mar.2005 Fish oil on canvas 250 x 360cm Mar.2005

The grey skinned fish is the dominant color, but for the explosion of red guts and blood of its flayed underbelly. Jinsong has moved from rendering multiple minute and colorful narrative vignettes that comprise his earlier works to huge canvases dominated by a single icon, starkly placed in the midground, with a nearly monochromatic palette.

The fish are a multivalent symbol, both in Jinsong’s work and in Chinese culture, though all of these rich associations are not consciously evoked. Jinsong explains that there are good and bad connotations, the first of which is the old Chinese tradition of fish representing plentitude, and by extension fertility. In the Chinese practice of word play relationships, fish as a homonym for happiness, becomes a talisman of luck, and mention might also be made of Zhuangzi the third century bce philosopher’s anecdote about how the fish are happy. Asked how he knew fish were happy, he responded, I know it standing here; that is intuitively. A familiar theme in traditional Chinese painting, fish nearly always are rendered alive and in motion in the water. So these flayed fish are closer in imagery to western tradition, still life paintings that are meant to symbolize momento mori, memories of death. The expressionistic style of paint with its passages of rich impasto underscores this association, perhaps best represented large paintings of rotting carcasses of beef by the Lithuanian-born French Expressionist Painter, Chaim Soutine (1893-1943). Complex in their associations, the Jinsong’s fish also evoke the political symbolism of the work of Bada Shanren (Chu Da), the late 18th century Chinese literati/individualist. Bada Shanren’s deeply distorted and unbalanced landscape settings provide the backdrop for schools of fish and cryptic inscriptions that allude to the inequity of the Manchu occupation of China. Viewers also read allusions to Bada Shanren ’s own tormented life into these troubled renderings.

Fish no. 7 113x138cm Mar.2006 oil on canvas Fish no. 7 113x138cm Mar.2006 oil on canvas

In this vein Jinsong’s fish are a metaphor for the troubles of modern society: the rampant destruction of the past, the mad consumerism, the exhaustion of natural resources, and the lack of humane concerns. Jinsong explains that artists have a responsibility to society to comment on the inequities and abuses suffered. In this way Jinsong may be seen within the literati tradition, whose artists felt it was their Confucian responsibility to express criticism of bad government policies, whether directly in their capacity as officials or privately in such artistic efforts as literature, calligraphy or painting. Often these personal works were emotional renderings, as the tenth century scholar-official, poet-painter Su Shih says of his bamboo paintings, he violently emits them after which he feels empty. In Jinsong’s wildly calligraphic manner of execution and subdued palette of shades of black, white and red, such literati allusions are clearly seen. It might also be mentioned that in traditional China fish, more specifically carp, represent the ambitions of the literati, told in so many popular stories. In the past fish ornaments too were official markers of rank in the form of decorative attachments worn on the belt.

Thus these oversize canvases, presenting a head on view of a gutted fish are a personal vehicle to present the social consciousness of the artist. Urging viewers to question the values of today’s world, Jinsong restores the ancient tradition of the literati in his contemporary paintings of urban life.

literature, calligraphy or painting. Often these personal works were emotional renderings, as the tenth century scholar-official, poet-painter Su Shih says of his bamboo paintings, he violently emits them after which he feels empty. In Jinsong’s wildly calligraphic manner of execution and subdued palette of shades of black, white and red, such literati allusions are clearly seen. It might also be mentioned that in traditional China fish, more specifically carp, represent the ambitions of the literati, told in so many popular stories. In the past fish ornaments too were official markers of rank in the form of decorative attachments worn on the belt.

Thus these oversize canvases, presenting a head on view of a gutted fish are a personal vehicle to present the social consciousness of the artist. Urging viewers to question the values of today’s world, Jinsong restores the ancient tradition of the literati in his contemporary paintings of urban life.

See Wang Fangyu, Richard Barnhart, and Judith Smith, Master of the Lotus Garden: The Life an Art of Bada Shanren (1626-1705) (New Haven: Yale Univ. Press 1990).

Su Shih 1037-101

When my empty bowels receive wine, angular strokes come forth

And my heart’s criss-crossings give birth to bamboo and rock.

What is about to be produced in abundance cannot be retained

And will erupt on your snow-white walls . . . .

See Susan Bush and Hsio-yen Shih, Early Chinese Texts on Painting (Cambridge Harvard Univ. Press,1985) , p. 218

|